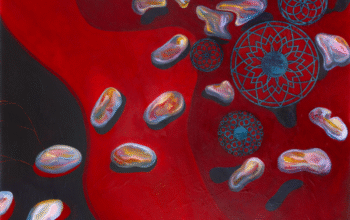

by Vannie Gama.

One of the good and bad sides of being an artist is studying other artists. The good side, because we explore our predecessors, not only as technicians but as lived experiences. The bad side, precisely, is when we discover the inconsistencies that are sold to us in the art world, when we observe the injustices and repetitive, ingrained historical erasures, which seem to take literally centuries to be dismantled. And it is curious, because these erasures and historical remodelings are frequent on a huge scale, a gradation of violence against entire cultures down to purely moralistic biographical “retouches.” Authors who in some way have already problematized this point were Hal Foster, Barbu, and Danto, since the 1990s in the sense of art history; after all, the critiques of “history written by the victors” have already been a well‑debated topic in studies of historicity at least twenty years before the deepening into art history itself.

Studying other artists (painters, writers, musicians, etc.), philosophers, scientists, and activists is an activity that began since I started reading, painting, and listening to music almost obsessively – back at 11, 12 years old. At 14, I began a collection of second‑hand books and the series “great painters.” At that time, unfortunately, there was no context to question perverse structures regarding everything that is not the normative presentation in the art world: a series only with white heterosexual men who, moreover, often exploited the image of other genders and ethnicities, inflating the discourse of “exoticism,” which beyond representation, allowed looting of artworks and archaeological items from countries, as well as exploitation of fauna and flora, and, evidently, delegitimization and hierarchization of knowledge, ways of life, and social structures of the Global South, Asia, and the Middle East. However, even without “naming names,” since we are speaking of the late 2000s and early 2010s, many things already bothered me in the stories of these great geniuses. Gauguin was the first book I removed from that collection, for example. For me, he is not a great master, neither in technique nor in history.

Many years later, in college, in Visual Arts there at 18 and 19 years old, doing my first exhibitions and leaving public libraries and second‑hand bookstores to have contact with people who were themselves revolutions, that is when I found myself and found another world of art. Some things, however, did not change. Leonardo da Vinci and Salvador Dalí continued to be those great giants. At that time I remained obsessed with literature, and devoured everything I could, even if I did not agree with half the content of the great books, which generally we are taught to idolize and only think of questioning much later. My smallness never prevented me from not swallowing stories and accepting very well‑established analytical standards, and that was great, because many years later, passionate about Dada and Surrealism, I could reread some biographies with a much more panoramic look and at the same time specialized in certain topics.

I believe it was in 2023 or 2024, at 26, that I wrote that article on Leonardo da Vinci’s scientific method, addressing what we already know of his sexuality, although there is still this attempt to preserve the image of a heterosexual Italian with the superhuman virtues of rationalism, when we can very well observe a da Vinci unstable in creative terms, nothing stoic, with period gossip and a fascination with his male loves. The same for the amorous adventures of Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and Gala. In 2022, when I was in the first year of my master’s, it was Marcel Duchamp’s turn. “Father of Dada.”

Dada is a movement that inspired me deeply and inspires me to this day, and not because of the great unshakable and serious actors, but because of the diaries, the poorly preserved creations, the plans never realized, and the inventive, impulsive spirit with an air of premonition or of an organization that was by no means the case at the time, and which even so, even with all the innocent and abrupt courage of a bunch of “half‑youngsters,” in fact established a new canon in modern art. A canon that is absolutely exhausting, indeed, since thanks to Dada’s openness regarding materiality, even today, 100 years later, what is “contemporary gallery art” is often the same attempt to remain in non‑convention as convention, with sculptures of materials that are “always very revolutionary” and give that face of contemporary art that is always the same thing: an installation made of three or four media, slightly interactive, with wide occupation of space, but with that strategic “clean look,” which disposes the non‑conventional, again, in the conventionality of the “clean” aesthetic, excessively organized and absolutely generic.

For me, true contemporary art does not necessarily reside in every form emulated to be that envelope. Once I was discussing with a professor who told me that “contemporary art” is a specific term that differs, almost by definition (although lacking one), from forms of urban art, digital art (I will include games here), and graphic art. What I mean by this is that not all art “in the semi‑random and pseudo‑inventive format of an installation with eccentric materials” is a common denominator for contemporary art, although it can be. And look, I am not against the use of non‑conventional materials, especially since when I did ”Prologue for Organic Observations’ (2023)’ I literally used insect shells on a white wall, with pseudo‑interactivity, too. The point I want to reach is the problem of isolating what was once new and trying, at all costs, to maintain that form. Again, this is not for all galleries and all institutions, but from what I consume of art, I would say that at least half of them seek to exhaust the visualities of the formula of installation‑of‑something‑with‑digitalities‑with‑non‑reproducible‑interactivity‑semi‑imagetic‑and‑nothing‑imaginary. What is different from this? Graffiti? A marble? A Graphic Novel? It is the project. It is the idea. That is what distinguishes. That made me study Maria Martins and Jota Mombaça, and it is what makes me equally admire Liniker, Debussy, and Lady Gaga.

An immense domestication: the icon needs to be immobile, inexpressive but a symbol of an unrepeatable expressivity; the contemporary needs to be clean, well‑presented, within everyone’s rules, with all the information necessary to create a beautiful narrative where the past of the work is brutal, but the present is with good posture, a glass of champagne at the vernissages, and a murmur never too loud, in good tone, avoiding the words that scream from the same works observed with almost an economic silence (economic, not religious, like that of the museum).

My favorite artists were unsilenceable, and at the same time, hypocrites. They are magicians with cheap tricks among other magicians, but divine and indecipherable to “others’” eyes. They are errant, even if at some point they cooperate with a system, after all, we need to eat. Some stories are sad, others are a little better. Banksy would know.

Duchamp was someone whom for a long time I adored and felt disgust for. There in the first year of the master’s, as I began to say a few paragraphs ago, we were immersed in classes of humanist geography, queer theory and decoloniality, new currents of the human sciences (it was not a master’s “in arts”), and there I had a bit more tools to develop my concerns than at the time of college, of the bachelor’s, a few years earlier. Already a great lover of Drag Art, beginning to carry myself as an artist and a researcher much more vocal about human rights, whether in politics (systemic, public) or in social issues (LGBT+ rights, indigenous rights, of the Black community, and gender equality in a world unfortunately so misogynistic and violent against women), I was able to revisit a great artist and in him recognize a reading of some artworks very different from those I had previously appreciated – there are indeed readings of Rrose Sélavy for a “more queer side,” but I wanted to go a little further and make an analysis truly grounded in the social sciences and queer theory of this other face of Duchamp. This work was published by the REDD journal of the São Paulo State University “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” the following year.

Two years after that article, I came across a call for Jo McLaughlin’s art history podcast. Her podcast is quite diverse in the themes of the art world, and constantly mixes reflective questions outside the theme into the episodes, making them not “simply didactic,” but philosophical, in an airy way and receptive to different readings of art history. We then recorded an episode about the queer side of Duchamp, at the beginning of 2025. The episode came out in September of the same year. We talked for more than an hour, and if I could, I would have talked even more. The last long conversation I had had with someone in that sense of interview was during Syntropy States, a project by Allie Joy, which, if I am not mistaken, we recorded in 2023. Both English, both extremely welcoming and experts in their fields. Although the world is full of conventions, it is in these authentic and independent projects that we strengthen ourselves in the present, rereading the past and thinking together about a near future, generally equally collective and empathetic, even if full of actions that go against the tales of the status quo – mixing disciplines, techniques, actions, and existences, and in this case, our stories and those of those who came before us.

The episodes are available (and our episode) everywhere. Feel free to choose your main audio platform: Rrose Selavy: Marcel Duchamp’s Female Alter Ego with Vannie Gama – Jo’s Art History Podcast | Podcast on Spotify or Podcast | Jo’s Art History.

See you soon!

And as a final note: Thank you for the space, Jo.

Would you like to receive the next post on your digital door?